We’ve mentioned that Agda is a proof assistant, i.e. a system in which one can write proofs that can be checked for validity much like one writes code whose validity is checked by a compiler. A proof as we know it is a sequence of formulas, each one could either be an axiom or follow from a bunch of previous formulas by applying some rule of inference.

In Agda and other systems based on the Curry-Howard correspondence there is another notion of proof, where proofs are programs, formulas are types, and a proof is a correct proof of a certain theorem provided the corresponding program has the type of the corresponding formula. In simpler terms, if one claims a proposition, one has to show the proposition (which is a type) is valid. A type can be shown to be valid if one can either construct an object of that type or provide a means (function) to do so.

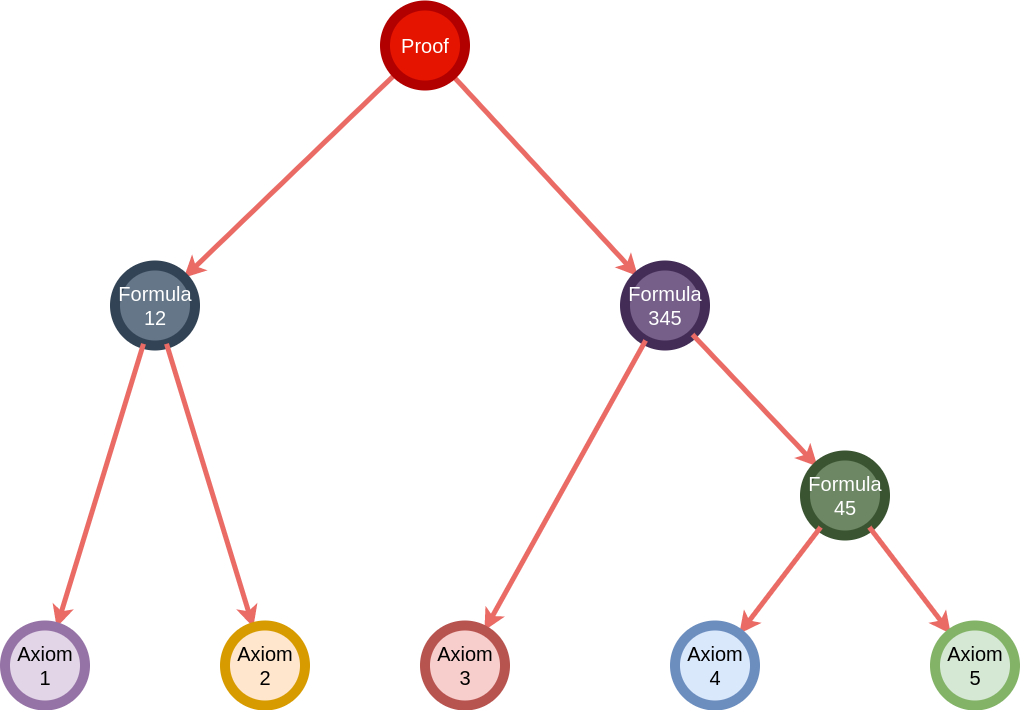

Thinking from the computer science perspective, a proof of a theorem can be modeled with a tree, where the root is the theorem, the leaves are the axioms, and the inner nodes follow from their parents by a rule of inference.

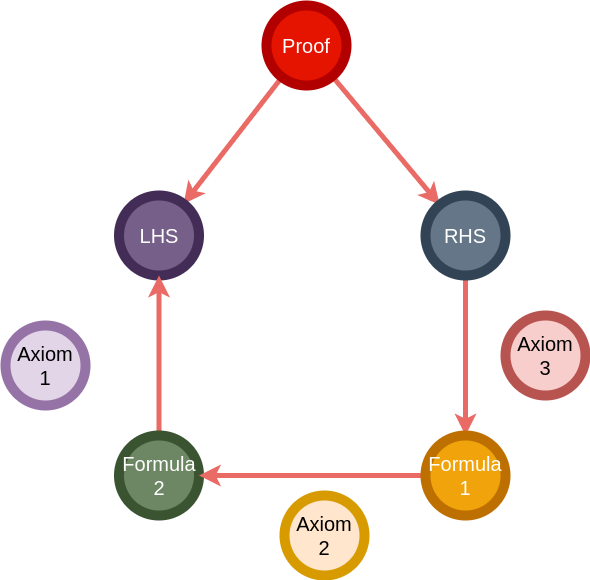

While proving a proposition that involves an equality, one may use one side of the equality (say, the right hand side RHS) to prove the other side. We shall see this method, called “equational reasoning”, in detail later.

module Types.proofsAsData where

open import Lang.dataStructuresHere we present some examples of how to write simple proofs in Agda.

For example, the <= operator can be defined using induction as consisting of two constructors:

ltz which compares any natural number with zerolz which tries to reduce comparison of x <= y, to

x-1 <= y-1:After applying lz sufficient number of times, if we end up at 0 <= x where

ltz is invoked, computation terminates and our theorem is proved.

data _<=_ : ℕ → ℕ → Set where

ltz : {n : ℕ} → zero <= n

lt : {m : ℕ} → {n : ℕ} → m <= n → (succ m) <= (succ n)

infix 4 _<=_Now, we can use that to prove a bunch of propositions:

idLess₁ : one <= ten

idLess₁ = lt ltz

-- (lt ltz)(one <= ten)

-- ltz (zero <= nine)

-- true

idLess₁₊ : two <= ten

idLess₁₊ = lt (lt ltz)

-- (lt (lt ltz))(two <= ten)

-- (lt ltz)(one <= nine)

-- ltz (zero <= eight)

-- true

idLess₂ : two <= seven

idLess₂ = lt (lt ltz)

idLess₃ : three <= nine

idLess₃ = lt (lt (lt ltz))If we try to compile something that is not true, the compiler will throw an error:

idLess' : ten <= three

idLess' = lt lt lt lt lt lt lt lt lt ltzproofsAsData.lagda.md:68,14-16

(_m_30 <= _n_31 → succ _m_30 <= succ _n_31) !=< (nine <= two) of

type SetThe odd or even proofs can be defined as in the previous proof. Here we successively decrement n till

we:

even₀ to prove n is evenodd₀ to prove n is odddata Even : ℕ → Set

data Odd : ℕ → Set

data Even where

zeroIsEven : Even zero

succ : {n : ℕ} → Even n → Even (succ (succ n))

data Odd where

oneIsOdd : Odd one

succ : {n : ℕ} → Odd n → Odd (succ (succ n))by which we could prove:

twoisEven : Even two

twoisEven = succ zeroIsEven

isFourEven : Even four

isFourEven = succ (succ zeroIsEven)

isSevenOdd : Odd seven

isSevenOdd = succ (succ (succ oneIsOdd))Equality of natural numbers can be proven by successively comparing decrements of them, till we reach

0 = 0. Else the computation never terminates:

data _≡_ : ℕ → ℕ → Set where

eq₀ : zero ≡ zero

eq : ∀ {n m} → (succ n) ≡ (succ m)Similar for not equals:

data _≠_ : ℕ → ℕ → Set where

neq₀ : ∀ n → n ≠ zero

neq₁ : ∀ m → zero ≠ m

neq : ∀ { n m } → (succ n) ≠ (succ m)To prove that a particular element of type A belongs to a list List' of type

A, we require:

x is always in a list containing x and a bunch of other elements

xsx ∈ list to x ∈ y + list₁, which either reduces

to

x ∈ x + list₁ which terminates the computation orx ∈ list₁where list₁ is list without y.

data _∈_ {A : Set}(x : A) : List A → Set where

refl : ∀ {xs} → x ∈ (x :: xs)

succ∈ : ∀ {y xs} → x ∈ xs → x ∈ (y :: xs)

infixr 4 _∈_Example:

theList : List ℕ

theList = one :: two :: four :: seven :: three :: []

threeIsInList : three ∈ theList

threeIsInList = succ∈ (succ∈ (succ∈ (succ∈ refl)))The relationship we saw earlier between formal proofs and computer programs is called the Curry-Howard isomorphism, also known as the Curry-Howard correspondence. This states that a proof is a program and the formula it proves is the type of the program. Broadly, they discovered that logical operations have analogues in types as can be seen below:

| Type Theory | Logic |

|---|---|

A |

proposition |

x : A |

proof |

ϕ, 1 |

⟂, ⊤ |

A × B |

A ∧ B (and / conjunction) |

A + B |

A ∨ B (or / disjunction) |

A → B |

A ⟹ B (implication) |

x : A ⊢ B(x) |

predicate |

x : A ⊢ b : B(x) |

conditional proof |

| \(\Pi_{x:A} B(x)\) | ∀ x B(x) |

| \(\Sigma_{x:A} B(x)\) | ∃ x B(x) |

| \(p : x =_A y\) | proof of equality |

| \(\Sigma_{x,y:A} x =_A y\) | equality relation |